Thirty-some years ago, when I was a single mom with little children, my lofty dreams for our future seemed permanently on hold as I coped with a series of low-paying jobs, an early 1900 wood-heat-only uninsulated farmhouse, and broken-down “vintage” cars. The floor of my 1958 Rambler station wagon was so rusted through in several places that I covered the biggest hole with the flattened lid of a garbage can. After the children watched me drive over it several times, we patched the hole in the floor. My 8-year-old daughter announced, “There, good as new again.” My children were raised without an indoor toilet and other necessities like a television, so my make-do philosophy ended up being part of their DNA also.

The urge to find relief from the ups and downs of such a hardscrabble life finally grabbed me in the middle of the night in the dead of winter. I snagged a pillow and a down sleeping bag I’d sewn when I was in my 20s, and leaving my children sleeping safely in their beds, I went into my backyard.

I made myself a bed on one of those silly, cheap, plastic chaise lounges beneath my children’s bedroom windows and settled in, still within earshot. Once the magical warmth of down feathers kicked in and I quit shivering, I noticed my new ceiling: millions upon millions of stars, the whole universe, galaxies and beyond.

Almost immediately, the round-and-round chatter in my head started shifting gears. I remember how beautiful the moon looked. “Good grief,” I said to myself, “my problems aren’t more important than the moon.” I felt diminished in a way that gave me immediate relief from the small stuff that tends to loom larger than life when you lose perspective and man-made walls and concerns close in on you.

As our lives become more and more hectic, more modern and hi-tech, it becomes increasingly difficult to spend time outdoors in nature’s clearinghouse, but outside is a lifeline. Our evolutionary molecules crave it. Children especially need it. It’s a simple solution to most of what ails us. It’s no wonder people fantasize that someday they’ll cash in their chips and buy a farm.

And thus began my mission. My story. The MaryJanesFarm story.

Properly groomed by my parents for what would lie ahead, Helen and Allen Butters’ little outdoorsy, suspenders-clad girl grew up with the desire to help others discover what she’d been given—the ability to fall into wild at any given moment.

My family of seven was ardently self-sufficient during the week—raising our own food and sewing our clothes.

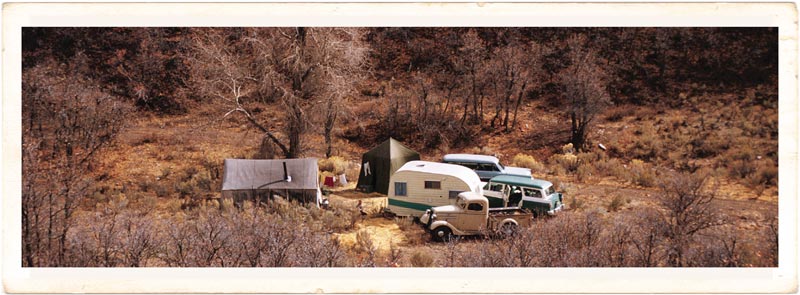

On weekends, we turned nomadic, taking to the hills and sagebrush flats of the West for the purpose of bringing home food. Like nomadic wanderers, we set up camp; fished; hunted deer, rabbits, and other edible critters; gathered pine nuts and firewood; slept on the ground in old army tents; and cooked on a campfire.

Sometimes, we hooked up with our aunts and uncles. Cut from the same cloth as my parents, their families also knew the worth of outside.

Longing for fertile ground of my own where I could raise my own flock of chickens, maybe a cow or two, and a family, I made my way north, working as a wilderness ranger, wrangler, fence builder, carpenter, forest-fire lookout, and milkmaid. The day I left home at age 19, my parents gave me a sewing machine; a case of home-canned peaches; a dozen eggs; and a metal box full of assorted bolts, screws, nuts, and washers. My father said, “Grab one of the ½-inch bolts and use it to push the contents around until you find what you’re looking for.” Allen was a man who spoke plain, taught mere, and lived modest. He turned his basement workshop into a home-school classroom by including us kids in problem-solving projects, always taking the time to praise accomplishments. At my father’s funeral, my sister’s son recalled visiting “Grandpa” right after mastering the alphabet song. My father grabbed his hand for a trip around the neighborhood. Up and down our street they knocked on doors, Jimmy performing his new A-to-Z talent. One year, we made our Christmas tree from empty cans, stacked and wired together. It’s certainly no wonder my brothers grew up to be welders and inventors and I became a carpenter.

The idea to formalize (by attending a trade school) what my father had taught me presented itself after I’d graduated from high school and drove past a construction site on a sunny day in the middle of winter. A few of the workers were warming their hands around a campfire they’d built, feeding the flames using the discarded lumber they were generating as they sawed and hammered together a new house. “Now, that’s my kind of job,” I thought. I’ve built fences in Wyoming, houses in Utah and Idaho, and a couple of barns, always finding smaller remodel jobs in between, mostly re-roofing work, wherever I landed, along with upholstery and seamstress jobs.

My need to find paid work in the outdoors continued, but before long, I was seeking something more alone, more remote.