Included in the circle of those who helped me find my way to my farm are two salty, tough, irreverent Idaho men who helped me “live my one wild life”: Emil Keck and Cecil Andrus.

Emil Keck was already an institution in the U.S. Forest Service when I showed up for duty at the most remote ranger station in the Lower 48, arriving in 1976 via a two-seater Cessna that landed in Emil’s horse pasture.

I was alone with my pilot. I had all my camp gear, some food, a few books, and my carpentry tools on board. We’d been flying for 30 minutes and were getting ready to drop 1,000 feet in altitude, down into a narrow canyon at the confluence of the Selway River and Moose Creek, 27 miles from road’s end, in the heart of Idaho’s Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness.

Sighting the grass landing strip, really a pasture, he banked and took a nosedive. I looked over for reassurance but noticed tendons and veins in his neck that hadn’t been there a moment before. Years later, my pilot that day, Greg Hill, would die during liftoff from that same spot where we’d landed.

After we unloaded my gear, I watched until his two-seater Cessna was just a speck on the forest horizon. That’s when the silence set in.

Absolute silence makes a sound. It’s a kind of lonely pulse we keep at bay with noise, but the first time you hear it, you know it. I think it brings us back to a time when we bathed in the open, long before cars and planes. I call it “the sound of alone,” and I’ve learned to let it comfort rather than haunt me.

Earlier, I’d been given a Forest Service key that would open all the ancient log buildings at the remote Moose Creek Ranger Station, boarded up since last December, where my home for the next two years would be a 14-by-16-foot canvas wall tent draped over a wooden platform with a privy out back. A Forest Service secretary had taken me aside and warned me about the Selway’s legendary outandouter, Emil Keck, the district’s fire-control officer.

My absolute silence was broken an hour later when Emil Keck stepped out of the wilderness and into my life. “And who the hell are you?” he asked. He was grabbing bloody ticks off his body and biting them in half. “I told those bastards to send me a journeyman carpenter, not a girl. You can spare us both some grief and walk on outta here.”

“... a rude Apollo of a man ... of nameless age, with flaxen hair and vigorous, weather-bleached countenance, in whose wrinkles the sun still lodged, as little touched by the heats and frosts and withering cares of life as a maple of the mountain; an undressed, unkempt, uncivil man, with whom we parlayed awhile, and parted not without a sincere interest in one another. His humanity was genuine and instinctive, and his rudeness only a manner.”

–Henry David Thoreau

He’d found me sitting on a stump in front of my tent, all my gear surrounding me. I stood and reached my hand out. “MaryJane Butters.” After shaking my hand, he asked, “What’s this?” pointing to the tool chest I had built while enrolled in trade school in Utah. It was lightweight but large, one foot deep, four feet wide, and three feet tall, with a clever side cut so that when the top opened, it lay on the ground. Inside, every tool had a special place, either carved from wood or fashioned from metal. Even the top handle was handmade.

“I’m not a journeyman carpenter. But those are my tools.”

Emil lifted the lid of my toolbox. With his scarred, crooked hands, he took out a few tools. He inspected my joints, made note that my hinges were bolted through, my chisels sharp, and then, with his trademark intensity, he said, “If you made this, you can stay.”

And thus began Emil Keck’s inspection of my life.

Emil was already a living legend by the time I arrived, and even though he was always telling upper management where they could put it, he was eventually praised at its highest levels, his leadership skills unparalleled, his wilderness ethics unmatched. The bureaucrats who gave Emil Keck grief because of his outspoken ways will leave few marks, but Emil and his passion for wilderness will last forever. Two years later, when my biological clock ticked loud enough to disturb the silence, I left. In my attic, I still have Emil Keck’s written evaluation of my work: “Butters has been the best station guard since 1963.” The day I left, my life forever changed, we stood alone at the trailhead. My pack was loaded up for the 25-mile hike out to a new life beyond, one that would forever bear Emil’s inspection of me, albeit self-imposed.

“Butters, if you ever need me, just ask. You’ve got big dreams. You’ll need money. As soon as I win the Reader’s Digest Sweepstakes, you’ll see me coming up your road with a gunnysack full. For now, here’s the shirt off my back.”

I still have the shirt he gave me that day, mended and stained. And I have a grown son named Emil, born on Emil Keck’s birthday, October 20.

Years later, after the birth of my first child, a daughter, I again walked the 27 miles, with her on my back, to visit Emil and Penny Keck at the Moose Creek Ranger Station.

I hear his voice often. “Butters, getting you to change your mind is like getting the Virgin Mary to change her underwear.” And I know, I’ve lived my life knowing, an Emil Keck maxim: wild country, what he called “the outback,” is the road home. It’s where humans find themselves; it gives you back to yourself. We can go into wild country and make it tame, make fields, and make roads go everywhere, but it is always there, just beneath our skin—longing for the light of day.

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, overcivilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wilderness is a necessity.”

–John Muir

Although his style was harsh and painfully direct at times, the two years I spent working with him 27 miles from the end of a dirt road became the basis for my life’s map—a code embedded with an intense can-do work ethic, tempered by an almost ministerial lend-a-hand attitude.

“We need the tonic of wildness, to wade sometimes in marshes where the bittern and the meadow-hen lurk; to smell the whispering sedge where only the wilder and more solitary fowl builds her nest, and the mink crawls with its belly close to the ground.”

–Henry David Thoreau

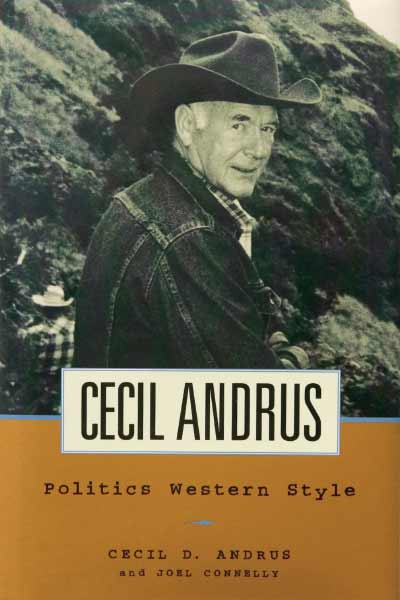

Cecil D. Andrus, Idaho’s four-term governor and former U.S. Secretary of the Interior, worked tirelessly to create designated wilderness areas throughout the West and Alaska during the era I lived and breathed wilderness. Through numerous additions to the national park system, the wilderness system, the wild rivers system, and national wildlife refuges, Andrus ensured the preservation of some 103 million acres in perpetuity. Those of us who are passionate about the need to preserve wilderness have benefited immeasurably from his Western style of politics when we’ve needed to take exception to public policy: take good aim and talk straight, Andrus style. Over the years, as I’ve lived in small remote towns throughout my state, his tough, strong stand on issues of preservation has touched the lives of every citizen I’ve known. Even Robert Redford said he misses having Andrus in office. Idahoans miss him. Thank you "Cece" for the great green splotches that show up on my Idaho maps.

“In wildness is the preservation of the world.”

–Henry David Thoreau