From its start in 1990, my backpacking food line has evolved over the years.

The message on the back of my 54-plus backpacking foods tells the story of how my company came to be, but it’s not the whole story. For all the years I dreamed of being a farmer, I never specifically dreamed the “value added” part of it, that well-loved marketing term used by rural economists when they talk about farmers coming up with innovative business ideas. Truth be told, I devised our little brown packages of backpacking food for one reason only: survival. For sure, I love to feed people and I’m good in the kitchen; my mother saw to that. But when I started selling packaged food, it was my rear end I was trying to save. And not just my rear end. I was moved by the plight of other farmers I know.

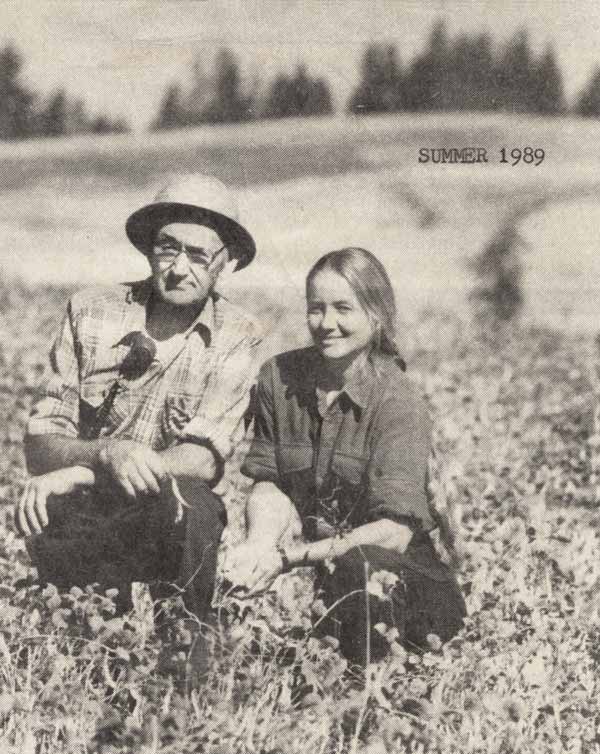

Picture this: it’s 1989 and several of us farmers (about 20) are sitting around a table in a restaurant. Most everyone there is a chemical farmer, but the conversation is about hope. We’d just finished up a tour of several farms where innovative cover crops or alternative food crops (around here that means anything other than wheat, peas, and lentils) were being tried.

“There must be some way out,” said Eric Wegner. The year before, he had planted 10 acres of organic peas in an experimental plot. “Frankly, it was a disaster. I lost them all to aphids.”

“Going 100 percent organic from the type of farming we’ve been doing is economically impossible on a large scale,” said Kathy Clemm, a farmer in the Troy-Deary area. “After using chemicals and fertilizers, the soil is no longer in the condition where it will produce like it would 30 or 40 years ago,” she added. “We don’t have the living matter we had in the soil. The soil pH is down to where the soil is host to weeds and pests, and we’ve killed off natural predators with pesticides.” Kathy wasn’t sounding too hopeful.

“Chemicals are getting damn expensive, the crops are getting worse instead of better, and insects and diseases are also worse,” said Charlie Bower, a Kendrick farmer.

Charlie Bower shows MaryJane his

organically grown bean crop.

(Moscow-Pullman Daily News, 1989)

He told us he remembered raising 50-bushel-an-acre wheat before World War II without the wonders of anhydrous ammonia fertilizer or weed and pest management by DuPont. We went on to lament that the only way a modern farmer can get 50 bushels from an acre of soil depleted by chemicals is to spend thousands and thousands of dollars (every year needing/spending more) on chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Charlie reminded us that the value of wheat (adjusted for inflation) has declined 82 percent since 1945. Along the way, government-funded farm subsidies have kicked in (chemical corporations influencing Congress), enticing farmers to continue to buy even more expensive chemicals.

Farmer Bob Lothspeich offered even less hope. “If we’re going to have the responsibility of raising crops cheaply, we’re going to have to have the chemical inputs to do it.”

Lacrosse farmer Jon Ochs, one of two organically certified growers in all of Whitman County (only a small portion of Ochs’ acreage was organic at the time, and he has since quit farming altogether) said, “Activist groups making broad demands on farmers to phase chemicals completely out of farming can cause more harm than good. They don’t have a clue how to effect that sort of transition.”

The oldest farmer in the bunch finally offered, “Well, it took us 40 years to get into this mess; it’ll take us 40 to get back out.”

I was new to the group, and they weren’t quite sure where I stood. Though a fellow farmer, I was the youngest farmer there, and also a known environmentalist, having founded the Palouse-Clearwater Environmental Institute (a going concern to this day). But I was talking hope, too. And I wasn’t pointing a finger like environmentalists often do. I professed a feel for the big picture. The “how did Monsanto, Cargill, and Archer Daniels Midland come to own all of us” big picture. And I agreed with the 40-year rule. This was the long haul. It would take all of us together, not just a few of us alone.

I saw these farmers were open to the idea of getting off the chemical treadmill, but without economic incentive, there were few rewards to be had. What they needed was hope, and I was determined to give it to them. Maybe I could be to chemical farming what Betty Ford was to drugs and alcohol. I wanted to show unconditional support, create a safe place, a starting place, a secure market. I also wanted to create a working business model for farmers. Rural sociologists speak “why value added.” I wanted to show “how value added.” Once I got rolling, I could bring farmers here for hands-on training. (Eventually, I did in fact, launch Pay Dirt Farm School, a nonprofit educational program that offered farm apprenticeships over the course of several years to some 60-plus people, most of them spending an entire summer, a few of them a year or more, experiencing first-hand the operations of our farm.)

Farm romance (Nick and MaryJane, spring 1994).

My starting place presented itself within a short time. I was still working as PCEI’s official director (a little bit farmer, little bit environmentalist, and little bit carpenter). Having progressed from passing the hat in a bar to bankroll my idea, to an annual budget of $100,000 (grant money and donations) in just a few years, we showed all the signs of permanence—a board of directors, employees, a copy machine—when a dark cloud of economic disaster headed our way. It was announced that the Russian wheat aphid was on its way to Moscow—our Moscow, not Russia’s Moscow. Local farmers were called to war, and to battle the intruder, the EPA had decided to allow the use of a banned chemical. Environmentalists were alarmed. Farmers now had a toxic, expensive chemical to pay for (stir, touch, breathe) and upset, worried mothers to deal with. A meeting was called in the Grange. As the parking lot filled up, the crowd inside became increasingly polarized, with about 30 farmers on one side, 30 concerned citizens on the other. As a representative of both groups—a farmer and a parent and an environmentalist—I saw how difficult it would be to implement the changes we all longed for in such an environment.

Nothing was resolved that evening, but a little seed had planted itself. (Actually, two little seeds—my future husband was sitting opposite me on the other side of the room.)

After the meeting, farmer Marc Jacobson of Pullman introduced himself to me. In his hand, he held a dark-brown miniature garbanzo bean called Aztec, or desi.

Garbanzo beans.

He explained that because of its thick, dark seed coat, it didn’t need pre-emergence chemicals, and because it had oxylic acid in its leaves, aphids wouldn’t touch the plant. He had witnessed clouds of aphids land on his experimental field, take a taste, swarm again, and leave. Plus, it didn’t mind lack of rain. He’d been growing this little-known variety for three years, but he was about to give up because he couldn’t find anyone to buy it. No one knew what to make of it. It was just too different from the salad-bar chickpea variety familiar to all of us, and the seed coat created a lot of dark bran when ground.

I knew there had to be a use for these hearty legumes. Within two days, my idea had gelled. I drove to Marc’s farm and brought home a 50-pound sack. I hand-ground all of it in my wheat grinder, bought about 20 different herbs and spices, and set out to create a “value-added” just-add-water falafel recipe.

I ended up buying all he had in inventory, about 700 pounds. Eventually that formula, along with the rest of my foods, went on to win Editors’ Choice from Backpacker magazine in April 2000.

My little value-added story gets even better. Next, I developed a recipe for green split-pea soup (made with local peas), tabouli (using local soft white wheat), and lentil chili (from local lentils). The foods weren’t 100 percent organic yet (remember the 40-year rule), but that was my goal. Along the way, I found another Palouse farmer, Rod Repp, who was growing organic peas, wheat, and lentils, but struggling financially.

Rod Repp and sons Kevin, 12, and Nathan, 10, track down weeds with a hoe, not spray.

National Geographic, 1995, Jim Richardson

Selling the kinds of crops he was growing as a raw commodity wasn’t paying his bills. He was starting to talk value-added, so I formed a corporation, thinking I could raise money through the sale of stock. Rod gave our corporate gas tank its first fill-up by trading a mountainous supply of yellow split peas for stock in lieu of money (neither of us had any). I started putting half yellow split peas into my falafel recipe, while Rod geared up to grow our first-ever organic Aztec garbanzo beans. My goal then was organic falafel. I got involved in the politics of organic agriculture and chaired Idaho’s first sanctioned “organic board” charged with writing rules and regulations for what “certified organic” meant. Modeling our first-of-its-kind program after California’s recently passed organic statutes, we were able to pass legislation that allowed Idaho farmers to legally say “Certified Organic by the State of Idaho” on our beans, peas, lentils, wheat, etc. I was Grower Number 8. Eventually, we realized I was also going to be Idaho’s first organic “manufacturer,” so we had to go back again to our legislators to adopt written rules regarding things like packaged soup mixes and other value-added foods like my falafel and lentil soup.

Unbelievably, our humble request was meeting up with resistance, so I hopped on an airplane for Boise to meet with Idaho’s legislators. To my surprise, our message of value-added wasn’t well-received, at all, to say the least. During a break in which I was sitting in the hallway with a legislator explaining why organic farmers weren’t the enemy, a towering figure from a large mainstream farm organization walked over to say to me, “You people charge more for your food and it isn’t any different than ours, so we’re going to see to it that you aren’t allowed to put the word organic on your packaged foods.” I came home defeated (our proposed rules didn’t get the votes they needed that day) but also determined to call my falafel “organic falafel.”

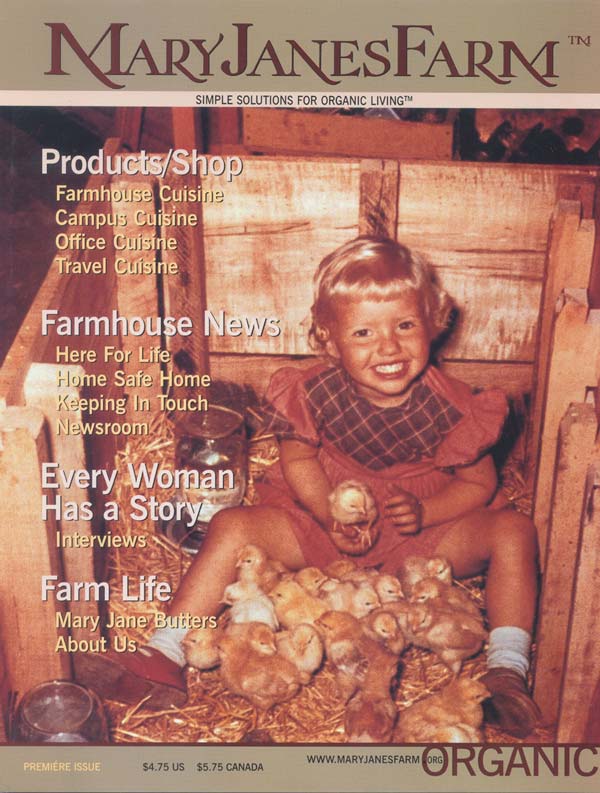

Premier cover of MaryJanesFarm magazine.

Along the way, I nearly went under several times, but I vowed I would never, ever wheedle a farmer down in price to survive, which means I had to “market” the hell out of everything in my heart. All my passions had to go down on paper—brochures, press releases, mail-order catalogs, any forum anywhere (remember this was pre-Internet, before blogs and Facebook). And I had to talk value until I was blue in the face.

The value-added part of my business grew and grew, modeled after a traditional, diversified farm—if the potatoes don’t bring in money, perhaps the barley will. Or in my case, how about an eponymous magazine, or maybe lamp shades or organic bed linens? Why not give writing books a try? Let’s open a B&B!

Sales of my backpacking foods are now sufficient to employ my family and friends. I employ local people (one of my stated, long-time passions) and the food is packaged here at my farm (every year, close to a million dollars’ worth of food leaves our farm on a UPS truck).

I have no desire to produce it in a factory, in a city, with little machines working the night shift. Which means, at some point, I might outgrow what we can produce here, meaning the world will need another farmer somewhere or farmers elsewhere to do what I’ve done. If you’re a farmer, or a future farmer, or a struggling farmer, hang in there. Remember the 40-year rule. Most importantly, tell your story. Eaters need to know. Buy a digital camera, a color printer, and a good computer. Value-add a pea the way I did, an herb, a kernel of wheat, a garbanzo bean. Another story, yet another presentation will get whipped up and served to eaters willing to listen, “get it,” and buy it—something akin to, if you don’t let me feed you, we both starve. My hope is that more and more people will continue to “talk it and walk it” (keep it out of the hands of big corporations, organic and otherwise).

If you’re an eater, buy some of my Curried Lentil Bisque or Loaded Comfort Potatoes.

If you’re contemplating an outpost adventure or simply needing something for the office, by all means, let us feed you. If you’re dining at home, try our farmhouse line. My foods come in non-aluminum, pouch-cook packaging or in bulk, which gets downright economical. Become an agrarian pioneer with us. Take it on an outpost trip and you’ll have it all, good food in a good place, all the while reassuring us farmer types that you really do want us doing what we do, making ready for your next scrumptious bite.

Organic Bare Burrito